Sound Healing – Ancient Sounds

By Annaliese and John Stuart Reid

Most ancient cultures used the seemingly magical power of sound to heal. Sound healing had almost disappeared in the west until the 1930s when acoustic researchers discovered ultrasound and its medical properties. With this discovery, research burgeoned and today the ancient art of sound healing is rapidly developing into a new science. (For information on sound healing in modern times please see our article ‘Rediscovering the Art & Science of Sound Healing.’)

Aboriginal Sound Healing

The Aboriginal people of Australia are the first known culture to heal with sound. Their ‘yidaki’ (modern name, didgeridoo) has been used as a healing tool for at least 40,000 years. The Aborigines healed broken bones, muscle tears and illnesses of every kind using their enigmatic musical instrument. Interestingly, the sounds emitted by the yidaki are in alignment with modern sound healing technology. It is becoming apparent that the wisdom of the ancients was based on ‘sound’ principles.

Sound Healing in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptian culture extends back to 4000 BC and they have a long tradition of vowel sound chant. A Greek traveler, Demetrius, circa 200 B.C., wrote that the Egyptians used vowel sounds in their rituals:

‘In Egypt, when priests sing hymns to the Gods they sing the seven vowels in due succession and the sound has such euphony that men listen to it instead of the flute and the lyre.’

The Corpus Hermeticum also contains a reference to the Egyptian’s use of sound as distinct from words. This book was probably redacted in the 1st century AD but it is believed to be much older, possible as early as 1400 BC:

In a letter from Asklepios to King Amman [he says]: ‘As for us, we do not use simple words but sounds all filled with power.’

The Egyptians believed that vowel sounds were sacred, so much so that their written hieroglyphic language contains no vowels. We can, therefore, safely assume that vowel sound chant carried a powerful significance for their priests.

Egyptian priestesses used sistra, a type of musical rattle instrument with metal discs that creates not only a pleasant jangling sound but, as we now know, also generates copious amounts of ultrasound. Ultrasound is an effective healing modality and is used today in hospitals and clinics so it is entirely possible that ceremonies in which many sistra were used were not merely employed to enhance the musical soundscape but were intended to enhance the healing effect.

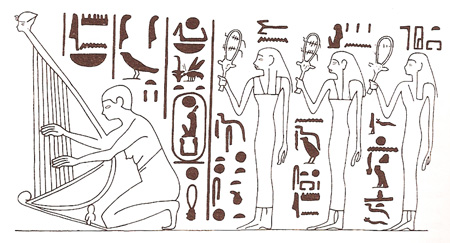

In the wall scene below, from a building erected by Queen Hatshepsut, three priestesses play sistra, accompanying a harpist, another instrument known to have healing qualities.

The healing chapel at Deir el-Bahari, Thebes, was dedicated to Amenhotep-son-of-Hapu, a deified healing saint closely associated with Imhotep—who is largely recognized under the title of ‘physician.’ Imhotep’s repute was so great that 1,500 years after his death the Greeks identified him with their healing god Asclepius. These two deified men—Amenhotep-son-of-Hapu and Imhotep—were usually worshipped together in the same Egyptian healing temples. John Stuart Reid’s acoustics research in the pyramids has provided strong evidence that the Egyptians designed their chapels and burial chambers to be reverberant in order to enhance sonic-based ceremonies. Reid underwent a significant healing of his lower back during his experiments in the King’s Chamber that he attributes to the resonant properties of the sarcophagus. He conjectures that the acoustic resonance was deliberately contrived by the Egyptian architects and thinks it very likely that they were aware of the healing properties of sound long before the Greeks.

Sound Healing in Ancient Greece

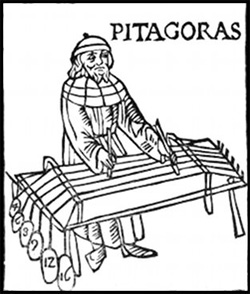

The Greek, Pythagoras (circa 500 BC) was, in a very real sense, the father of music therapy. The Pythagoras Mystery School, based on the island of Crotona, taught the use of flute and lyre as the primary healing instruments and although none of Pythagoras’ writings have come down to us we know of his philosophy and techniques from many contemporary writers. With his monochord—a single-stringed musical instrument that uses a fixed weight to provide tension—Pythagoras was able to unravel the mysteries of musical intervals.

Iamblichus noted that:

‘Pythagoras considered that music contributed greatly to health, if used in the right way…He called his method ‘musical medicine’…To the accompaniment of Pythagoras’ his followers would sing in unison certain chants…At other times his disciples employed music as medicine, with certain melodies composed to cure the passions of the psyche…anger and aggression.’

In the Greco-Roman period healing temples were used for ‘incubation,’ a process in which patients underwent ‘dream sleep,’ among other known modalities. It seems likely that music was used therapeutically during their stay. The reverberant spaces of the healing temples and sanatoria would have enhanced the therapeutic aspects of musical instruments, mainly a function of the parallel-facing stone walls.

The Sanatorium at Dendera, Egypt

Note the small cells where patients would undergo dream sleep incubation and music therapy

Returning to the use of vowel sound chant—the production of vocal sounds rather than words—many eastern cultures developed variations of chant for healing and for spiritual ascension. Studies have shown that vowel sound chant can bring about many positive physiological changes in the body, and create an altered state of consciousness in which the chanter becomes serene.

An example, among many cultures that use vowel sound chant, are the Tibetan monks who have a tradition extending back at least a thousand years. One of the earliest western scholars to reach Cathay (modern day Tibet but then a province of China) was Sir Gilbert Hay, the architect of Rosslyn Chapel, near Edinburgh, Scotland. It is assumed that Sir Gilbert would have encountered the monks in Cathay and their now famous gong-making science.

By sprinkling sand on a gong, then striking the central area, tuning in ancient times (and even today by some makers) is achieved. If the resulting sand patterns were asymmetrical the gong maker would continue to shape and beat the metal.

As a musical instrument the gong has wonderful healing properties because it contains virtually the whole spectrum of audible sound. Human cells, immersed in the gong’s sound field, absorb the frequencies they need—a kind of sonic food—and reject what is not needed.

We cannot know for certain whether Sir Gilbert brought back this healing knowledge to Scotland but anyone who has experienced the wonderful acoustics of the Rosslyn Crypt will know that this is not accidental.

It is also likely that Sir Gilbert acquired cymatics knowledge in Cathay that he employed in creation of the Rosslyn Cubes. These are cube-like carved stone structures that decorate the ceiling of the Lady Chapel and in which he embedded a sacred melody in cymatic sound symbols. Thomas and Stuart Mitchell recently decoded this music and it takes the form of the beautiful Rosslyn Motet.

In conclusion, sound healing has a rich tradition reaching back thousands of years although following the Tibetan monk’s experiments with sound healing in the 1400’s there is a gap of around 450 years during which this ancient art seemed to almost die out. It wasn’t until 1936 that our story of sound healing in the modern era begins.

Content courtesy of John Stuart and Analiese Shandra Reid

Copyright (c) 2011. All Rights Reserved.

https://www.cymascope.com