In an important breakthrough in deciphering dolphin language, researchers in Great Britain and the United States have imaged the first high definition imprints that dolphin sounds make in water.

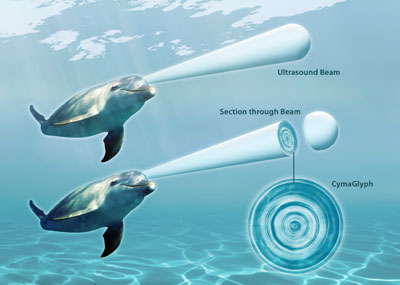

The key to this technique is the CymaScope, a new instrument that reveals detailed structures within sounds, allowing their architecture to be studied pictorially. Using high definition audio recordings of dolphins, the research team, headed by English acoustics engineer, John Stuart Reid, and Florida-based dolphin researcher, Jack Kassewitz, has been able to image, for the first time, the imprint that a dolphin sound makes in water. The resulting ‘CymaGlyphs,’ as they have been named, are reproducible patterns that are expected to form the basis of a lexicon of dolphin language, each pattern representing a dolphin ‘picture word.’

Certain sounds made by dolphins have long been suspected to represent language but the complexity of the sounds has made their analysis difficult. Previous techniques, using the spectrograph, display cetacean (dolphins, whales and porpoises) sounds only as graphs of frequency and amplitude. The CymaScope captures actual sound vibrations imprinted in the dolphin’s natural environment—water, revealing the intricate visual details of dolphin sounds for the first time.

Within the field of cetacean research, theory states that dolphins have evolved the ability to translate dimensional information from their echolocation sonic beam. The CymaScope has the ability to visualize dimensional structure within sound. CymaGlyph patterns may resemble what the creatures perceive from their own returning sound beams and from the sound beams of other dolphins.

Reid said that the technique has similarities to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs. ‘Jean-Francois Champollion and Thomas Young used the Rosetta Stone to discover key elements of the primer that allowed the Egyptian language to be deciphered. The CymaGlyphs produced on the CymaScope can be likened to the hieroglyphs of the Rosetta Stone. Now that dolphin chirps, click-trains and whistles can be converted into CymaGlyphs, we have an important tool for deciphering their meaning.’

Kassewitz, of the Florida-based dolphin communication research project SpeakDolphin.com said, ‘There is strong evidence that dolphins are able to ‘see’ with sound, much like humans use ultrasound to see an unborn child in the mother’s womb. The CymaScope provides our first glimpse into what the dolphins might be ‘seeing’ with their sounds.’

The team has recognized that sound does not travel in waves, as is popularly believed, but in expanding holographic bubbles and beams. The holographic aspect stems from the physics theory that even a single molecule of air or water carries all the information that describes the qualities and intensity of a given sound. At frequencies audible to humans (20 Hertz to 20,000 Hertz) the sound-bubble form dominates; above 20,000 Hertz the shape of sound becomes increasingly beam shaped, similar to a lighthouse beam in appearance.

Reid explained their novel sound imaging technique: ‘Whenever sound bubbles or beams interact with a membrane, the sound vibrations imprint onto its surface and form a CymaGlyph, a repeatable pattern of energy. The CymaScope employs the surface tension of water as a membrane because water reacts quickly and is able to reveal intricate architectures within the sound form. These fine details can be captured on camera.’

Kassewitz has planned a series of experiments to record the sounds of dolphins targeting a range of objects. Speaking from Key Largo, Florida, he said, ‘Dolphins are able to emit complex sounds far above the human range of hearing. Recent advances in high frequency recording techniques have made it possible for us to capture more detail in dolphin sounds than ever before. By recording dolphins as they echolocate on various objects, and also as they communicate with other dolphins about those objects, we will build a library of dolphin sounds, verifying that the same sound is always repeated for the same object. The CymaScope will be used to image the sounds so that each CymaGlyph will represent a dolphin ‘picture word’. Our ultimate aim is to speak to dolphins with a basic vocabulary of dolphin sounds and to understand their responses. This is uncharted territory but it looks very promising.’

Dr. Horace Dobbs, a leading authority on dolphin-assisted therapy, has joined the team as consultant. ‘I have long held the belief that the dolphin brain, comparable in size with our own, has specialized in processing auditory data in much the same way that the human brain has specialized in processing visual data. Nature tends not to evolve brain mass without a need, so we must ask ourselves what dolphins do with all that brain capacity. The answer appears to lie in the development of brain systems that require huge auditory processing power. There is growing evidence that dolphins can take a sonic ‘snap shot’ of an object and send it to other dolphins, using sound as the transmission medium. We can therefore hypothesize that the dolphin’s primary method of communication is picture based. Thus, the picture-based imaging method, employed by Reid and Kassewitz, seems entirely plausible.’

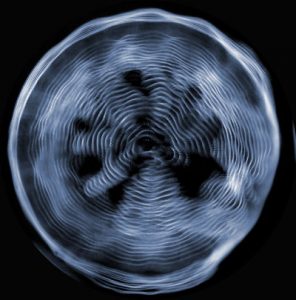

The CymaGlyphs of dolphin sounds fall into three broad categories, signature whistles, chirps and click trains. There is general agreement among cetacean biologists that signature whistles represent the means by which individual dolphins identify themselves while click trains are involved in echolocation. Chirps are thought to represent components of language. Reid explained the visual form of the various dolphin sounds, ‘The CymaGlyphs of signature whistles comprise regular concentric bands of energy that resemble aircraft radar screens while chirps are often flower-like in structure, resembling the CymaGlyphs of human vocalizations. Click trains have the most complex structures of all, featuring a combination of tightly packed concentric bands on the periphery with unique central features.’

The CymaGlyphs of dolphin sounds fall into three broad categories, signature whistles, chirps and click trains. There is general agreement among cetacean biologists that signature whistles represent the means by which individual dolphins identify themselves while click trains are involved in echolocation. Chirps are thought to represent components of language. Reid explained the visual form of the various dolphin sounds, ‘The CymaGlyphs of signature whistles comprise regular concentric bands of energy that resemble aircraft radar screens while chirps are often flower-like in structure, resembling the CymaGlyphs of human vocalizations. Click trains have the most complex structures of all, featuring a combination of tightly packed concentric bands on the periphery with unique central features.’

Regarding the possibility of speaking dolphin, Kassewitz said, ‘I believe that people around the world would love the opportunity to speak with a dolphin. And I feel certain that dolphins would love the chance to speak with us – if for no other reason than self-preservation. During my times in the water with dolphins, there have been several occasions when they seemed to be very determined to communicate with me. We are getting closer to making that possible.’